Greg Howell

Introduction

As a wine consulting laboratory business, now with labs in five States of Australia, we deal with many wineries and many thousands of wines every year. Most of these wines are of good quality; however a very small minority have some issues that need our help. Our job is to investigate what has gone wrong in the wine, and to suggest potential ways to fix the problem. Below are a few cases that have come through our doors recently and hopefully this analysis will help other winemakers avoid similar issues. It is worth pointing out that in one case there was nothing wrong with the wine, but with how the sample was taken.

Problem wines

1. Wine full of wild yeasts and moulds

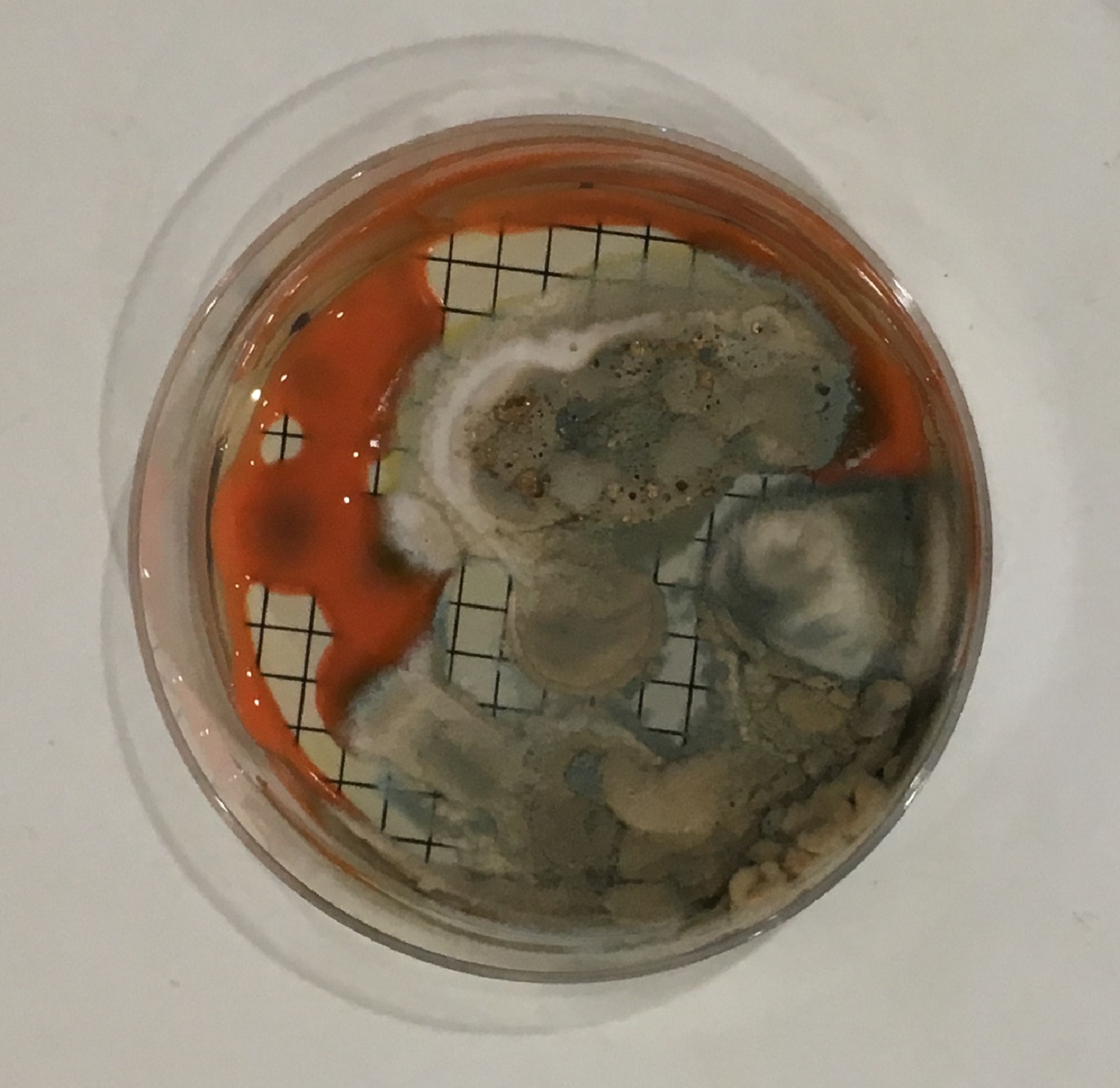

Some recent tank samples tested for microbial growth turned out to grow a veritable zoo in the lab! See Figure 1.

In this sample we found moulds and yeasts including some “lovely” Rhodotorula yeast species. Rhodotorula have very striking orange/red colonies when grown on a plate. Moulds are not normally found in wine and further discussion with the winemaker suggested the wine was stable, well sulfited and was expected to contain no microbes at all! Further discussions revealed that the sample had been taken from a small sample valve on the tank. The drain line of the valve was inspected and found to contain drops of wine inside the outlet. Closer inspection also found mould growing in the sample point outlet.

It was obvious that the sample was not representative of what was in the tank. Sampling is a critical part of any analysis and sample containers, sample valves and any other devices that come into contact with the sample should all be clean and preferably flushed with the sample before filling. In particular, sampling points on tanks should be washed, brushed or flushed. The simplest way is to run a few litres of wine through the point before the sample is taken. Another way to ensure clean and disinfected sample points is to have a squirt bottle of 70% ethanol/distilled water handy. This is a common disinfecting reagent used in microbiology labs and is an easy, no fuss and effective way to flush and disinfect sample points before taking a sample. It is a common misconception that the stronger the ethanol solution, the better it is at killing micro-organisms. In fact, a 70% ethanol solution is more effective at killing micro-organisms than a stronger solution because the presence of water is thought to assist in the denaturing of proteins in micro-organisms. After cleaning the sample point, a small volume of wine should still be run through the sample point before filling a sample bottle.

Lesson: getting a representative sample of any wine is a critical part of any analysis. Ensure all sampling equipment (bottles, sample points etc.) are clean, flushed and/or disinfected before taking a sample.

Figure 1: the plate resulting from the microbes present in the sampling point – but not in the wine in the tank!

2. Difficult to filter wine

Several 2016 wines were sent recently for analysis just prior to bottling. The winemaker suspected that there were Botrytis effects in the wine and was concerned about filtration issues prior to bottling. Glucans are a long chain polysaccharide that are produced by Botrytis and can cause filter blocking, so glucan tests were done.

Only one of the wines showed high levels of glucans and would certainly have caused filtration issues. We recommended that the winemaker use an enzyme treatment (Rapidase Batonnage) for removing glucans. This enzyme has glucanase activity and reduces the level of glucans in a wine.

Lesson: if fruit has Botrytis infection, glucans are normally formed in the wine. The presence of glucans can have serious impacts on subsequent filtration of the wine. A simple test can confirm if this is going to be an issue. Effective treatment by glucanase enzymes can solve the problem.

3. Hazy white wine

A white wine was recently submitted that had a haze. A microscopic examination was done on the isolated deposit and yeast and bacteria were found. After discussions with the winemaker about the process used to make the wine, the haze was suspected to also contain pectins, as pectolytic enzymes had not been used in the production process. A pectin stability test was performed and it was quite clear that there were pectins in the wine. A further bench trial using a clarification enzyme (Rapidase Clear) removed the haze. The clarified wine was then much easier to handle and the residual microbes easily removed.

Lesson: don’t underestimate the usefulness of standard enzyme treatment in white wines and ensure you use the recommended doses.

4. Wine from mouldy fruit

Some lab testing was done on several wines that a customer had bottled and sold but had subsequently deteriorated in the bottle. The fruit for these wines had some mould and Botrytis issues at harvest in 2016 and the winery was interested to know what compounds were present compared to a clean wine so that “marker” compounds could be used in future.

The main analysis performed was for gluconic acid: this is a very good marker of fruit affected by Botrytis. The oxidative enzymes in Botrytis, e.g. Laccase, oxidise glucose to gluconic acid. Levels of this acid in clean fruit and wine are typically less than 0.5 g/L. Higher levels can be used as a guide to the level of Botrytis infection.

Laccase analysis was also requested, however this common test is not quantitative and has often raised concerns amongst oenologists and winemakers as to its effectiveness as a predictor of Botrytis infection in fruit.

The gluconic acid results varied from less than 0.5 g/L to over 1.0 g/L. Laccase results were all very low – clearly this was not a good guide. The gluconic acid results can be used as a guide to the level of Botrytis infection and the winemaker did advise that the wines were of varying levels of stability. It was seen that the gluconic acid data was more helpful than the more typically tested laccase in correlating with the incidence of botrytis in the vineyard.

Lesson: a better way to check Botrytis levels in juice and wine is to use gluconic acid as an indicator rather than the less precise laccase test.

Conclusion

A number of potential wine problems can be identified or solved by some simple and cost effective lab tests. These tests can also point to an effective treatment for removing the concern. Several problems that have been observed in our labs have been discussed in this article and hopefully some lessons learnt. Sampling techniques of wine from tanks were found to be causing some issues that weren’t representative of the wine in the tank. And in some other cases the use of enzymes in winemaking to remove pectins and glucans solved some issues encountered. A newly utilised test for gluconic acid was also demonstrated to be a better guide for wines affected by Botrytis.

Greg Howell is the founder and Managing Director of Vintessential Laboratories. He can be contacted by email on [email protected].

Copyright© 2017 Vintessential Laboratories. No part of this publication may be reproduced in any form or by any means without the permission in writing from the copyright owner.