Fizzing Red and Tartrate Stabilisation – Testing Times – June 2017

This month – Red Wine Fizzing and Tartrate Stabilisation with CMC

Vintessential Laboratories are dedicated to helping our winery customers discover winemaking problems early, understand them, and then fix them. At our five laboratories around Australia we test hundreds of samples every week, so there’s hardly a problem we haven’t seen.

Every month we bring you some of the recent problems that have been sent to us and explain how, working with our clients, we managed to solve them.

Red wine fizzing when bottles opened

Recently a customer brought in a bottled red table wine that exhibited some fizzing when opened. The wine had been wild fermented and the customer asked us to check for the presence of any yeast in the bottle and also for the levels of the main metabolites that could referment in the bottle, namely glucose, fructose and malic acid. We also recommended checking the pH and sulfur dioxide levels.

Interestingly, the malic acid was below the detection limit but the sugars were above the detection limit of less than 0.1 g/L. Of course these results represented what was in the bottle at the time we received it, but they may have been present in higher concentrations at the time of bottling, but then consumed by yeast in the bottle. The pH was fine, but the sulfur dioxide level was a bit low.

All this didn’t tell us much, but did make us a bit suspicious. Next the wine was plated out on both yeast and bacteria media and the winemaker had a nervous week’s wait whilst any bugs had time to grow.

Fortunately for the winemaker, no bacteria or Saccharomyces yeast grew. (It is worth remembering that as well as being a winemaker’s best microbial friend, Saccharomyces can also be an enemy – if it is allowed to grow in the bottle – which it can and does).

Most unfortunately, however, a great swathe of Brettanomyces did grow.

Growth of Brettanomyces on agar plate

So the culprit that caused the fizzing was the dreaded Brett! This was made possible due to the lowish levels of sulfur dioxide, the trace amounts of sugar and the fact that the wine was not sterile filtered at bottling. We did also check the molecular sulfur dioxide levels and they were well below the recommended 0.8 ppm. Luckily the volatile phenols 4EP and 4EG were low, which is not unexpected if the cells recently became viable. And interestingly the wine had an alcohol over 15%. Yes, Brettanomyces is a very hardy little beast…

Upon further discussion, the client revealed that he didn’t normally like to wait 10 days for plating to see if the wine was sterile at bottling so took a risk and didn’t get any testing done. However, now there are very reliable PCR techniques that can be done within a day, so there is a good solution for those winemakers under time pressure.

Now that the cause of the fizz in the bottled wine had been sorted, the winemaker is implementing an intensive testing program for Brett in all his barrels. From now on, he will also use the PCR technique for detecting Brett so that fast results can be obtained.

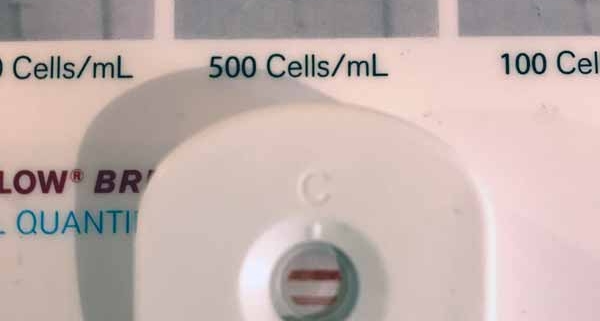

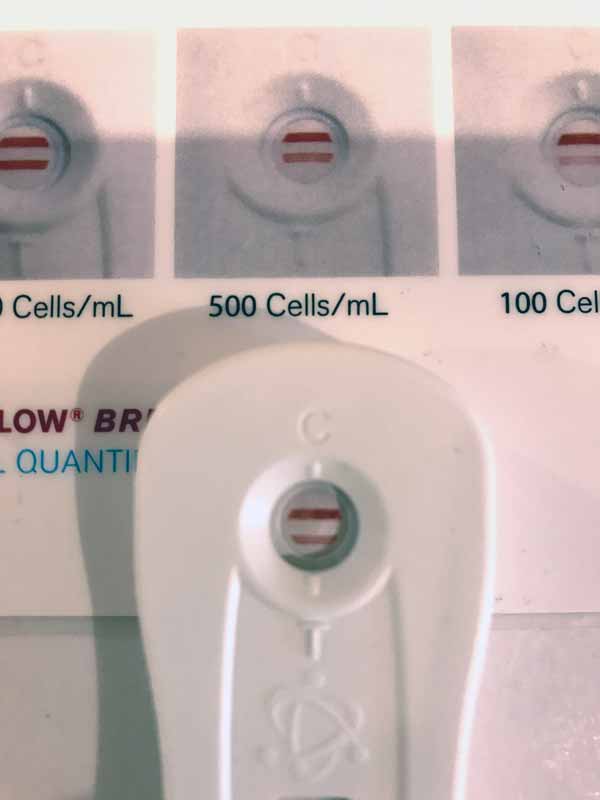

Amount of Brettanomyces as shown on PCR test

Unfortunately for this particular wine the only course of action is to get the wine out of the bottles, treat it, sterile filter it and then rebottle. This, of course, is quite an expensive exercise and one that could have been avoided if a good monitoring program was in place initially. And of course if the sugars were tested and a safe limit of less than 0.1 g/L was adopted before the wine was declared totally finished and safe for bottling, this issue would have been extremely unlikely to have occurred.

This level of sugars used to be difficult to determine accurately at such low concentrations, but now with low cost spectrophotometers and inexpensive enzymatic test kits there is no reason why all wineries, no matter how small, can adopt this method of testing. As can be seen above, there is a real risk if the safe limit of less than 0.1 g/L sugars is not adopted. Of course if the winery doesn’t want to do this testing itself, it is bread and butter work for commercial wine labs.

At the winery in question, we expect a much more rigourous approach will be taken in future.

By the way, this is not a rare wine spoilage example – we wonder who will be next to get some unintended fizz in their life?

In Store: Brettanomyces by PCR

Related Articles: PCR – a new test in the battle against Brettanomyces spoilage yeast in wine

Tartrate stabilisation with CMC

There are now several ways to ensure that no potassium hydrogen tartrate (KHT) crystals end up in finished wine. The traditional technique of cold stabilising by chilling wine to below zero degrees and holding for days is a slow and expensive operation, particularly due to the high cost of electricity.

Nowadays there are a couple of other ways to achieve KHT stability that involve using additives that inhibit the formation of the KHT crystals. These techniques don’t remove the KHT crystals (as cold stabilisation does), but does inhibit their formation. One product type is based upon CMC (carboxy methyl cellulose), while the other involves using a mannoprotein extract from Saccharomyces yeast.

A client recently asked for our help in the use of a CMC product that he hadn’t used before. He was attracted to the product as he believed it was a cheap and easy way to tartrate-stabilise his wine. So we performed 6 day cold stability trials in our lab to determine the best dosage rate of the CMC to use. The wine also had to be tested for us to ensure the wine was protein-stable by using the heat stability test. These tests were, of course, an extra cost to the winemaker.

Once the appropriate level of CMC was determined, the winemaker added the product to his wine and then waited 3 days for the process to work. One of the wines did develop a slight haze which we were asked to investigate. Whilst we were doing this work on the haze, the wine in the cellar had cleared up considerably, although a higher turbidity as measured in NTUs did result.

To add further effort and expense, the winemaker was advised by the bottling company that the wine needed to be filtered twice.

These extra steps, whilst necessary, did add extra costs and the winemaker was concerned that the initial low price for the CMC product was only one factor in the overall cost of making the wine KHT stable.

He is now considering trying a mannoprotein product for his next wine as he understands that although the initial price may be higher than CMC, there is less work and cost required to achieve the tartrate stable wine.

Conclusion

The use of rigourous testing protocols are necessary if winemakers are to avoid problems in their wine from Brettanomyces spp. spoilage. With the advent of low cost spectrophotometers and new techniques such as PCR, inexpensive, rapid and accurate testing techniques can assist greatly in avoiding such problems. In the case of new winemaking products, there is always a learning curve and some unexpected costs and work that may not be obvious initially such as in the example above with the use of CMC for tartrate stabilisation.

Greg Howell founded Vintessential Laboratories in 1995; he can be contacted by email on [email protected]/.